"It's the Inventory, Stupid!"

When it comes to ticketing, access to inventory trumps technology

So far in my career I’ve worked with more than a few companies trying to take on the concert ticketing industry, from scrappy startups to multi-billion dollar international conglomerates. The opportunity seems clear: Everyone hates the status quo! Ticketing fees are egregious! (N.B. I’ve written before about how things aren’t as straightforward as they seem when it comes to ticketing fees.)

The first thing I ask anyone heading down this path is “how will you obtain the tickets to sell?”. Without a clear answer to this, any efforts will be dead in the water.

More often than not the answer is something along the lines of “we’ll build the best ticketing platform ever, which will attract artists, which will attract fans, which will attract more artists, [etc…]” No. Stop. It doesn’t work like that.

Whose ticket is it anyway?

Whilst it’s true that fans will flock wherever they need to in order to buy tickets, it’s rare that the artist controls this decision. More often than not it’s the promoter and/or the venue, and even this is dependent upon the territory in question.

That’s why vertical integration remains such a powerful force in live music. If you’re a promoter that owns a ticketing company, you can allocate your own inventory to your own vendor. This guarantees volume, which is the lifeblood of any ticketing platform. You can have the best technology in the world, paired with the slickest user interface, but without ticket inventory to sell you’re a shop with empty shelves.

Even independent ticketing companies have relied on strategic investments and relationships to secure their initial inventory. Take DICE, often positioned as the artist and fan-friendly alternative in the ticketing world. They didn’t bootstrap themselves into relevance through pure product. In their very early days, they took strategic investments from some of the most influential artist managers and booking agents in the UK. These are people who could funnel high-demand shows, and therefore meaningful ticket inventory, into the platform. The product mattered, sure, and at the time mobile-only dynamic QR-code based tickets were genuinely revolutionary, but their access to the tickets they sold mattered more.

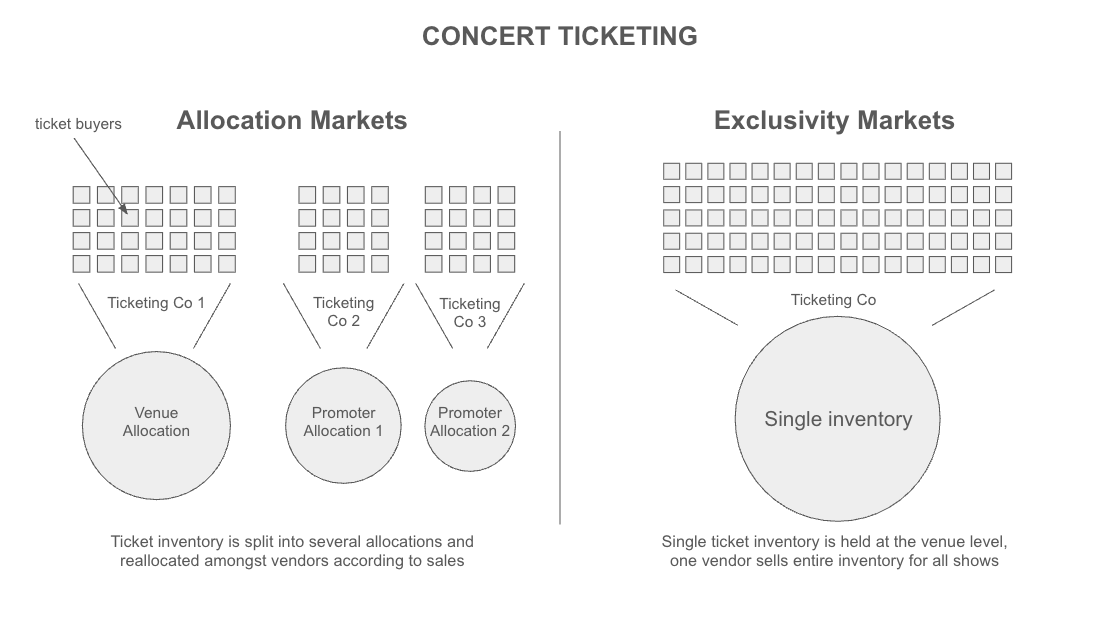

Then there’s the question of markets. In the UK (and many parts of Europe), ticketing is an allocation market. Multiple vendors might be selling tickets for the same show, each with a slice of the total inventory. The venue will typically want to sell a portion (usually around 50%), and the promoter will typically control the rest. Crucially, the promoter will often spread their allocation around multiple vendors in order to make use of the organic reach of each. That creates openings for new entrants: if you can persuade a promoter or artist to hand you an allocation because you have an audience, you can start selling immediately, even without exclusivity. It’s no coincidence that the larger standalone challengers of recent years, DICE and See Tickets, both originated from the UK.

Contrast that with the US, where ticketing is largely an exclusivity market. Venues typically sign long-term exclusive deals with a single ticketing company in return for a hefty advance. If you don’t control the venue contract, you’re locked out of selling tickets for their shows. That means any challenger has to attack at the level of the venue deal itself. This is a big lift which comes with an equally big price tag. You need cash to fuel the advances, which means you’re constantly playing catch up with what you’ve already outlaid.

The historic loophole here has been the artist “fan club” presale allocation, which CrowdSurge, Seated and others have used to obtain inventory. Venue ticketing deals in the US did, traditionally, allow for the artist to take a sliver of the tickets (~8 to 10% of the house) off the venue’s platform in order to be sold directly to their “fan club”. If you could power these artist presales on behalf of artists, then you could start to build a ticketing business in the States without needing to sign up venues directly. Whilst the practice continues to this day (and can be a meaningful source of tickets in allocation markets), venues and promoters are growing increasingly reluctant to release this inventory. N.B. the 2015 lawsuit between Songkick and Live Nation centred around the allowance (or not, as the case may be) of this practice.

In any case, if you want to build a truly global ticketing business, you can’t ignore exclusivity markets forever. They’re where the majority of the world’s ticket revenue flows, and where the biggest margins lie. Which brings us back to the first question: how do you get the tickets? Because no matter how good the tech, without inventory there’s nothing to sell.

Breaking the chain

For now, vertical integration is the iron law of ticketing. Whoever controls the inventory controls the economics, and that control flows from promoters to venues to their chosen ticketing partners. If you control all parts of this chain, happy days! But history shows us that integrated systems rarely last forever. They’re stable until they’re not. Until some combination of technology, regulation, or consumer behaviour pries them open.

Clayton Christensen described this dynamic as the Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits: when one stage of the value chain becomes over-integrated and earns excess profits, it creates an opportunity for another stage to be modularised and for new entrants to capture value by integrating around a different bottleneck.

“Formally, the law of conservation of attractive profits states that in the value chain there is a requisite juxtaposition of modular and interdependent architectures, and of reciprocal processes of commoditisation and de-commoditisation, that exists in order to optimise the performance of what is not good enough. The law states that when modularity and commoditisation cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.”

— Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Solution

A useful comparison is the airline industry. For decades, airlines controlled not just the planes but also the distribution, often selling exclusively through their own counters or select travel agents. That was vertical integration in action. The shift came with the rise of global distribution systems (GDS: Amadeus, Sabre, Galileo, Worldspan), which modularised airline inventory and made it bookable through any travel agent or, later, online portals like Expedia, Skyscanner and Kayak. Airlines still own the planes, but the economics of distribution have shifted towards whoever captures demand most effectively.

Concert ticketing today looks a lot like airlines pre-GDS. Promoters and venues bundle inventory with their chosen ticketing partners, keeping supply locked in tightly integrated systems. For a challenger, the opportunity isn’t to build a “better airline counter” (a shinier version of Ticketmaster) but to imagine a GDS-style model for concerts: supply modularised, tickets sold through many channels, with value flowing to whoever best activates demand.

That would be a radical realignment: tickets treated as a commodity, with economics rebalanced towards those who actually drive awareness and sales. Artists, DSPs and fan communities could start to economically benefit from the awareness they create, rather than the incumbents who merely control the pipes. Christensen’s law suggests that it’s only a matter of time before concert ticketing’s attractive profits are conserved somewhere else.

What would it take?

If concert ticketing is to undergo its own airline moment, two shifts in particular would have to happen.

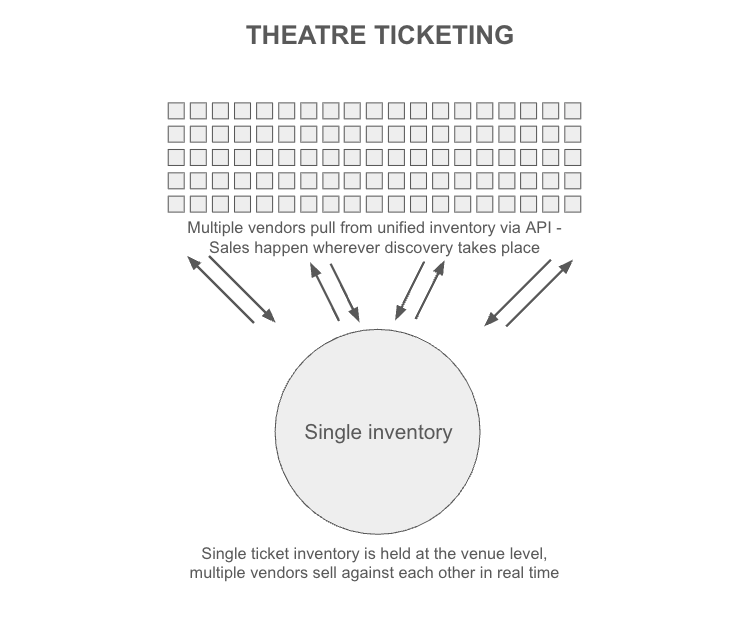

First, common rails for ticketing inventory. Today, each ticketing system is a silo, with its own exclusive pipes into a venue or promoter’s allocation. That locks supply into closed systems. Imagine instead a set of open APIs that pulled from the same inventory and made tickets available wherever discovery happens. This could be Spotify, TikTok, YouTube, an artist’s mailing list, or a venue’s own website. In that world, the “checkout” layer becomes modular: tickets flow like commodities through many front doors, and the platform that generates demand captures the economics.

This would be akin to what we already see in the world of theatre, where anyone with an audience can set themselves up as a vendor and start selling tickets in return for a chunk of the booking fee.

“For me the future of ticketing is having a system that’s similar to the one that’s used on the West End or Broadway where we’ve got one inventory of tickets that people can access through an API and we can all sell it in real time. Then I’m not going to be reliant on a Ticketmaster or an AXS or whatever but I can go to anybody that’s got a massive database and go “hey, do you want to sell my tickets?” Because you can make a little bit of money out of selling them plus you can offer it as a service to your customer.”

- Stuart Galbraith, CEO of Kilimanjaro Live, on the Promoter 101 podcast

Second, artists insisting on data control. The irony of modern live music is that promoters rarely “promote” shows in the literal sense anymore. In a social media era, it’s largely the artist who drives demand and awareness of their shows. Promoters are increasingly financiers and logistics coordinators. If the artist is the one generating sales, then why should they cede control of the ticket buyer relationship (and the ticketing fees that currently sit outside of the artist - promoter show deal), to a third-party ticketing company? If artists demand to own their fan data and to sell tickets alongside the venues and promoters they work with, the locus of control begins to shift.

Neither of these changes will come easily. Ticketing incumbents have every incentive to keep the system closed, and promoters will be reluctant to give up the leverage they still have. But Christensen’s law is clear: when excess profits are concentrated in one part of the chain, pressure builds elsewhere. If discovery platforms and artists align around open rails and data ownership, the vertical integration that defines ticketing today may finally give way to a more modular, demand-led future.

In ticketing, technology will always matter, but without inventory it’s worthless. The question is when, and how, control of that inventory finally shifts.